The increasingly unacceptable faces of capitalism.

The corporate world has seldom been held in more contempt than right now. It goes far beyond Qantas and PWC to strike at the heart of the way global business functions.

Stephen Schwartzman is very well paid. Very well. Last year, he took home $A617 million in ‘compensation’ for his efforts in running a large US private equity firm, Blackstone. Dividends from his share holdings made him even richer: all up, he made over $A2 billion last year.

According to the Forbes Billionaires List, his wealth amounts to over $A48 billion. In all the world, 35 people are richer than he is and 8,050,000,000 – or thereabouts – are poorer.

|

| Schwartzman and an employee |

Stephen Schwartzman certainly doesn’t like taxes. When the Obama administration proposed a tax increase that would affect people like him, he likened it to Hitler beginning World War 2. “It's a war,” he said. “It's like when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939.”

The extraordinary magnitude of executive pay in the United States is the result of an entire economic system being captured by a small, exclusive caste of corporate mandarins. These firms are no longer run with customers, staff and even shareholders in mind. Schwartzman’s take-home pay in 2022 was 987 times as much as Joe Biden’s. But he was hardly alone in harvesting the largesse.

Company size has relatively little to do with the amount executives are paid. Only four of those ten companies are among America’s top 100. Pay seems to have much more to do with the power an executive wields within the outfit even than profitability. Other, more durable, measures of success – customer engagement, staff satisfaction, public esteem – are far less significant.

The dominant culture of the United States fosters this mentality. Its history abounds with corporate robber barons: railroads in the 19th century, oil in the 20th century, computers now. Other western countries, which have different cultures, have nevertheless followed this lead.

Executive pay is a fairly transparent way of measuring the state of corporate culture. Australia is a long way behind the US but there is little doubt about where we’re heading. In 2022, Australia’s highest-paid CEO was paid 43 times as much as the Prime Minister. Since then, she’s had a raise of 28%.

Again, pay packets don’t seem to correlate with company size and performance. An example is the property group Charter Hall, whose market capitalisation puts it at number 97 on the Australian Stock Exchange but whose CEO last year was the seventh highest-paid. The share price has been generally underwhelming: after a short-lived peak in 2022, at the time of writing (September 2023) it was down by 20% over the previous 12 months, underperforming the ASX 200 index by 75%. And the price remained lower than it had been before the Global Financial Crisis in 2008.

But times change. Faith in the profit motive has almost vanished in Australia.

The Roy Morgan polling company began monitoring pubic attitudes to the corporate sector in early 2019, asking whether people thought the profit motive made companies deserving of trust – or not. Even then, the answer was a resounding ‘not’. Now, four years on, distrust is even more entrenched, as this Morgan chart shows:

“The poor behaviour of many of Australia’s corporate leaders reveals a moral blindness to what is ethical and in the community’s interest rather than solely in the shareholders’ interest,” the pollsters noted.

Who is the economy for?

But Australia’s, and the world’s, economic malaise goes far deeper than corporate poor behaviour. It’s about who the economy exists to benefit – everyone, or just a few?

The trend toward ‘just a few’ has accelerated sharply. If we look at the proportion of gross domestic product going to employees, and to company profits, we can see that workers are getting substantially less than at any time since these records began in 1959 and profits have never been higher.

Actually, it’s worse than that. As Ross Garnaut, the eminent Australian economist, explains, the huge benefits paid to executives are actually counted as wages: “The increase in the profit share and the fall in the wage share is actually bigger than the statistician makes it look. When Qantas paid CEO Joyce tens of millions in recent times, that would be mostly classified in the wages and not the profit share.”

For any economy to work effectively, there must be a balance between the amount of national wealth going to labour and to capital. If the owners of capital don’t get enough, their capacity to invest in new enterprises, or to expand and improve existing ones, is diminished. And if workers don’t get enough, they don’t have money to spend. Demand for goods and services falls and the economy collapses.

Either way, nobody in the long term benefits from the sort of imbalance we’re experiencing at the moment.

In the 1970s, the imbalance went the other way. Militant unions and frequent strikes drove wages up and up and company profits, therefore, down. Some unions behaved very badly: the most egregious example was perhaps the demarcation dispute, in which two unions went on strike against the other over the alleged poaching of members. Employers were caught in the crossfire.

The Labor governments of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating addressed those problems and restored a level of balance between labour and capital. The main vehicle was a series of Accords between the government and the union movement under which unions gave up extreme wage demands in return for a ‘social wage’ – economic measures to control inflation, social programs like Medicare and free public hospitals, and tax cuts for people on low incomes.Employers were not part of the Accords but benefited enormously. By the time the Keating government lost office in 1996, after years of painful but essential reform, the industrial relations system and the economy in general were working. In particular, there was no overall benefit from trying to tilt the balance between labour and capital either one way or the other.

But the political pendulum had swung. Over the next 21 years, conservative Liberal-National governments were in power for all but six. Beginning under John Howard and his Industrial Relations ministers, Peter Reith and Tony Abbott, there was a unrelenting assault on union power and on the ability of employees to take industrial action. For two decades, economic power swung away from employees to the corporate sector.As a direct result of those policies, income inequality in Australia increased dramatically. Between the beginning of the Howard government in 1996 and the mid-point of the Abbott-Turnbull-Morrison government in 2018, the gap between the richest and poorest 10% increased from $52.45 (measured in international 2017-equivalent dollars) to $88.34. In percentage terms, that’s an increase of 68%.

Few people in Australia have been unaffected by these changes. Most of us are worse off than we would have been otherwise. That’s been a driving factor in the relative improvement in public attitudes to unions, and in corresponding disdain for big companies and their executives.

Political scientists at the Australian National University have run extensive surveys of voter attitudes in correlation with every federal election since 1990. Over that time, the proportion of people thinking unions have too much power has plummeted – from 69% in 1990 to 40% in 2022. Now, over 70% of respondents think it’s big companies that are the problem.

These trends also show the political dangers of overreach. Fear of unions sank to its lowest level in 2007, when the Howard government’s radically restrictive WorkChoices policies became a major factor election issue. The government was bundled out of office and Howard lost his seat in parliament.

The vampire kangaroo

The Macquarie Group is one of Australia’s leading success stories. Or not, depending on your point of view.

Treasurer Paul Keating’s attempts to increase competition among banks gave Macquarie its big opportunity. In 1985, a smallish Australian offshoot of a British merchant bank, Hill Samuel, got a banking licence and changed its name to Macquarie Bank.

They developed a method of turning limited capital into maximum return. Macquarie would buy an ailing company relatively cheaply, then cut costs, sell off some assets and then put all or some of the slimmed-down, apparently efficient enterprise back onto the stock market. But they retained a long-term management contract which ensured very large fees were paid to Macquarie, whether or not the re-floated firm made profits for its new owners.

Because so much of that income went to senior managers, Macquarie quickly became known as the Millionaires Factory. And that was when a million dollars meant something.

In 1989, Margaret Thatcher privatised Britain’s water supply and sewerage systems, following the hard-right ideology that the ‘free market’ was always more efficient than any government-owned enterprise could ever be. So, just as the Russian oligarchs piled into the sell-offs of state enterprises by the economic geniuses working for Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s, the free-marketeers of the western world piled into the riches of Thatcher’s Britain.

|

| Please do not swim |

It was not a success.

Maintenance was not done. The pipes leaked. Sewage spilled. Complaints piled up and anger mounted. In 2006, RWS sold London’s water and sewerage to Macquarie for £8 billion ($A15.3 billion).

Macquarie raised another £1 billion ($A1.9 billion) for an investment program but the problems continued. Leakage from water mains was somewhat reduced but remained far too high. But under Macquarie’s ownership, Thames Water became the most heavily fined company in Britain for pollution offences: by 2013, it had been prosecuted for 87 events and fined £842,500 ($A1.6 billion).

The worst was yet to come. In 2017, it was fined £20.3 million ($A38.8 million) for discharging almost 1.5 million litres of untreated sewage into the Thames. The company also admitted other water and sewage offences in Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire.

Judge Francis Sheridan (pictured) was scathing about the company's “continual failure to report incidents” and "history of non-compliance.”“This is a shocking and disgraceful state of affairs,” he said. “It should not be cheaper to offend than to take appropriate precautions. I have to make the fine sufficiently large that [Thames Water and Macquarie] get the message … One has to get the message across to the shareholders that the environment is to be treasured and protected, and not poisoned.”

But it continued. Adequate maintenance was still not done. The fines continued but they seemed to be regarded by the company as a cost of doing business. Throughout the hot, dry summer of 2022, when people were trying to cool off at rivers and beaches, it discharged raw sewage 110 times. Incidents lasting 1,253 hours were recorded, but that’s certainly a significant under-estimate. The company only monitored 62% of its overflow points.

|

| Wikramanayaka ... the $30m CEO |

Thames Water made huge dividend payouts to shareholders – in other words, to Macquarie. Up to 2017, debts more than tripled from £3.2 billion ($A6.2 billion) to £10.5bn ($A20 billion) as Macquarie borrowed against its assets to increase dividend payments. Over just 11 years, an estimated £2.8 billion ($A5.4 billion) was paid to shareholders by this loss-making, polluting company.

In 2017, Macquarie sold Thames Water to a Canadian pension fund and the Kuwaiti sovereign wealth fund for three times as much as it paid in 2006.

But then, early last year, the British government allowed Macquarie to take over Southern Water, which serves counties around the south and south-east coast of England. It’s an area that includes many of Britain’s most popular beaches and seaside resorts including Brighton, Worthing, Hastings and the Isle of Wight as well as revered ancient towns like Winchester and Tunbridge Wells.

In the British press, Macquarie is frequently referred to as “the vampire kangaroo”. An article in The Times recently summed up the public’s feeling in the heading “Macquarie chiefs lived in luxury as debts piled up”. And Thames Water’s recently-resigned former CEO, Sarah Bentley, warned repeatedly that the company had been “hollowed out over decades”.

Judging by the tone of the British press, there is no confidence at all that Macquarie will serve the people of south-east England any better than it served the 15.5 million people of London.

Back home in Sydney, though, the executives are doing very nicely. In the most recent financial year the CEO was paid $30.4 million, a rise of 28% on the paltry $23.7 million she got the year before and 57 times Anthony Albanese’s salary.

The chief commodity trader, Nick O’Kane, had an even better year. He got $42.7 million, beating the PM by a multiple of 79.

Directors did pretty well too. None of those serving a full year got much less than $400,000. The chair, former Reserve Bank governor Glenn Stevens, got $872,903, which should be a handy supplement to his pension from the bank.

There’s more than one vampire kangaroo

Nobody – in this country, anyway – can quite match Macquarie for moral blindness and ravenous greed but some come close. The finance industry does this stuff very effectively.

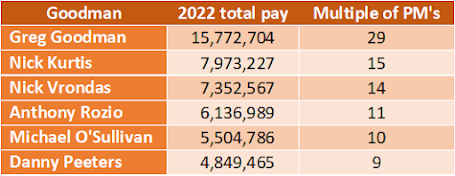

One such is the Goodman group, a commercial property investment manager that started as an offshoot of Macquarie but which has since done very well on its own. In 2022, its profit was up by 48% on the year before. The founder and CEO, Greg Goodman, got almost $16 million – not as good as his opposite number at Macquarie, but not bad: 29 times better than Anthony Albanese.

Australia’s own bank

In 1911, the Labor government of Andrew Fisher figured the new nation needed a publicly-owned bank to counter the effects of the private institutions. But although the Commonwealth Bank began as a savings and trading bank, in 1920 it also became Australia’s reserve bank, taking over responsibility for issuing money and further expanding its monetary policy role during the second world war.

In 1960, under the Menzies Liberal government, a new Reserve Bank took over central banking role, returning the CBA to its original, more mundane, role. As time passed, the rationale for having a government-owned commercial bank seemed to fade and in 1991 Paul Keating’s Labor government sold it off.

The CBA has long abandoned its origins as a key financial institution with the main aim of primarily serving the interests of the people of Australia. It, like other big companies, serves the interests of executives, directors and shareholders.

It’s the second-biggest company on the Australian Stock Exchange (after BHP) but, having endured a very bad decade of scandals that engulfed all the major Australian banks, salaries are surprisingly modest. The CEO, Matt Comyn, had to make do last year with a payout of only $10.4 million. Still, that’s 19 times better than the Prime Minister.

The banking royal commission is over but the big banks remain poisonously unpopular with the Australian public. The rorts and illegalities the commission uncovered – fees charged to dead people, money laundering, lying and cheating across a wide spectrum – have not been entirely forgotten.

And when people are struggling to pay mortgages, are slugged 20% interest on credit card debt and endure fees on everything but the air itself; when they consider the 1,600 branches that have closed in the past five years, learn about the shabby treatment of staff, look at the rewards enjoyed by those at the top, and hear about the CBA’s profit of $10.8 billion in the last financial year, unpopularity is to be expected.

Criminal casinos: triads and money launderers

The two big casino operators, Crown Resorts and Sky City, pushed the envelope of acceptable conduct even further than the banks. By 2019, the scandals had come to a head with a series of investigative reports in Four Corners, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age on money laundering, kickbacks, dealings with Chinese triads, and blatant exploitation of problem gamblers.

Crown’s share price reached it high point, $17.84 in January 2014, giving it a market capitalisation of $13 billion – in today’s dollars, that’s $16 billion. But then the rumours of malfeasance became more difficult to ignore and, in September, Four Corners ran a detailed account of the criminal activity at the company’s casinos. It reached its low point of $8.24 in October 2020, a decline from the peak of 54%.

|

| Packer at one of the Royal Commissions |

“In Macau there's evidence that Chinese organised crime gangs are heavily involved in organising the flow of high rollers into casinos. A recent US congressional report highlighted one estimate that a stunning $202 billion of ill-gotten funds are channelled through Macau each year.”

Crown’s strategy involved a subsidiary in Macau with links to where that money came from – triads and other organised crime outfits, drug money, prostitution and people trafficking. To clean that money, high-rollers were given junket tours to Crown’s casinos bearing mountains of cash. They would then put that money through the VIP gaming rooms, losing some but taking most out again as apparently legitimate winnings.

James Packer, the heir to Kerry Packer’s empire, stepped down as chairman of the Crown board in 2016 but has been blamed by two Royal Commissions for creating the culture of greed, exploitation and criminality that eventually brought the outfit down.

But in 2018 Crown, though on the nose, was still functioning normally. Relations with governments, particularly in Victoria, remained snug. The top executives who were overseeing the crime and corruption were being paid very well. And as executive salaries have at least doubled since then (in Macquarie’s case, tripled) they’d still be doing very well – if the whole thing hadn’t imploded.

Eventually, last year, Crown Resorts was sold to Stephen Schwartzman’s company, Blackstone, for the fire-sale amount of $8.9 billion. James Packer walked away with $3.3 billion. According to the Forbes billionaires list, he now has total wealth of $4.06 billion: a decent nest-egg but, by billionaire standards, unspectacular. Packer is now Australia’s 18th richest person and number 1,194 in the world.

It's a bit of a comedown: in 2013 he was the country’s third richest. But even that was a tumble from the status of his father, Kerry, who for decades was the richest and probably the most powerful Australian.

|

| Barangaroo's gaming room .. closed for business |

The high-roller floor at Barangaroo is now closed. At some time, it will open and again make a lot of money. How clean will that money be this time?

We can reliably expect Blackstone to wait out the aftermath of the scandals and Royal Commissions, sell off more assets and then return Crown to the stock market as a newly efficient, clean and respectable outfit worth a multiple of the $8.9 billion it paid. And the whole adventure is costing Schwartzman’s company only $3.5 billion of its own money.

Fossil fuel follies

There’s a slogan on the front cover of the latest annual report from Santos, the giant gas and oil company. “Creating a better world,” it says, “through cleaner energy”.

Natural gas is almost entirely composed of methane, the most potent of greenhouse gases. It is cleaner, in climate terms, only in the sense that coal is dirtier. Most reliable estimates say it has about two-thirds of the impact of coal extraction and burning.

As Australia’s Climate Council points out, there’s more to the gas pollution story than burning it in a stove. Methane and carbon dioxide are released in huge quantities during extraction, venting, flaring, and leaks in pipelines and equipment. Fracking, practiced by Santos, is especially problematic: gas can leak from fractured land well away from the well site and almost always unmonitored.Then there’s the process of liquefying gas for export, which burns up massive amounts of energy – most of it produced from fossil fuels.

“When fugitive emissions are considered alongside the immense quantities of fossil fuel-based energy used by the gas industry to liquefy gas for export,” a Climate Council paper says, “the reality is that gas is often no better for the climate than coal.”

But there’s money in it.

The war in Ukraine, and sanctions on Russian oil and gas, pushed up the world price during 2022 to around four times its usual level. Santos, already a highly profitable company, became even richer. So did its executives and directors.

In 2022, net profit after tax rose by 228% to $6.5 billion. Production volume increased by 73%, as they raced to exploit those very high prices.

Directors did well too. The chairman, Keith Spence, got $390,065. He’s also on the board of another mining company, IGO, which paid him $175,000.

Santos has more than its share of enemies.

|

| Farmers lock the gates |

The president of NSW Farmers, Xavier Martin, said the project would destroy some of the most fertile soil in the country.

Another farmer group blocked Santos trucks from accessing the Wondoba state conservation area near Gunnedah for six hours before being removed by police.

There have been dozens of similar protests, as well as more spectacular actions by the environmental group Extinction Rebellion.

There have been some wins. Last year the Federal Court handed a victory to traditional owners on the Tiwi Islands, off the Northern Territory coast, dismissed an appeal by Santos to an earlier decision preventing the company from continuing, for now, with a massive offshore drilling project.

Woodside also has big plans to expand gas production.

|

| Woodside's enormous expansion plans |

“Woodside’s Burrup Hub gas project is Australia’s biggest new fossil fuel proposal,’ said Greenpeace. “It would extract massive amounts of gas from under the ocean floor in northwestern Western Australia – with around 80% slotted for export overseas as liquefied gas (LNG). The Hub includes the Scarborough and Browse offshore gas fields, a second processing train at the Pluto onshore gas processing facility, and a 50 year extension to the life of the North West Shelf onshore gas processing facility.”

As the trend toward cheaper renewables gathers pace, the long-term viability of such a project diminishes. It’s a matter of time before they become stranded, worthless assets.

For now, though, the gravy train rolls on.

Woodside’s directors are doing fairly well too. Richard Goyder was paid $807,438 for his gig as board chairman. He also chairs Qantas, which earnt him another $750,000.

Around the world, the purpose of corporations has changed. Until the 1980s it could still be said that all stakeholders – staff, shareholders, customers, the broader community – had rights to be considered. No more.

Today’s big companies have a clear hierarchy of purpose and benefit:

- The CEO and the top half-dozen or so executives.

- Directors.

- Shareholders.

- Customers.

- Staff (other than those at the very top).

Executive pay: forever upward?

Pay peanuts, says the adage, and you get monkeys.

That’s the standard reason trotted out by corporation boards around the world to justify their otherwise indefensible largesse to senior executives and directors. There’s cut-throat competition, you see, for all our wonderful people and we have to match what other companies, in other countries, might pay to lure them away.

This is how the Goodman annual report puts it:

“Competitors seek to recruit our high-performing people around the world. Goodman’s remuneration strategy, featuring a long-term incentive plan that includes the whole team, has been a key driver of our success, and ability to retain talent globally.”

It’s an unstoppable race to the top. And the top is, of course, in the United States, where CEOs and other top people take away astounding amounts of money. Remember Stephen Schwarzman of Blackrock? Last year, the “compensation’ for his efforts in a single year was $616 million.

Unless all this stops, that’s where Australia and the world are heading. Except that when we get there, the posts will have been moved. By then, Steve and his buddies will be getting even more.

Controlling the grifters: the door to reform is wide open

“How much does it cost to bring down a prime minister?” asked The Sydney Morning Herald’s chief political correspondent in 2011. “The answer: a tad over $22 million.”

That’s what the mining industry paid for a campaign to overturn Kevin Rudd’s proposal to tax the excess profits of the big miners – BHP, Rio Tinto, Fortescue, Gina Rinehart, Clive Palmer, Santos, Woodside and the rest.

The Rudd government had proposed taxing the windfall profits that the minerals companies were deriving from sky-high commodity prices. These minerals are, after all, the property of all Australians. The miners buy the right to exploit them in return for paying royalties based on normal prices. That does not – or should not – entitle them to profits so massively out of whack with the royalties they pay.

A strident campaign, brandishing one of Tony Abbott’s three-word slogans (Axe the Tax) engaged Australia’s most renowned ad-man, Neil Lawrence (who created the Kevin 07 campaign for Labor in 2007) and Bill Hunter, the avuncular Australian actor and life-long Labor supporter. The government’s campaign was stilted, dull and uninspiring.

|

| Rinehart ... she doesn't like paying tax |

In the aftermath, Rudd was rolled. A new measure was negotiated with the minerals industry by the new Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, and her resources minister, former ACTU president Martin Ferguson. It raised very little in extra tax and was abolished in 2014 by the incoming Abbott government.

|

| Ferguson ... unionist, minister, lobbyist |

Windfall profits such as those fought for by the miners are known to economists as “rent”. The idea is that in any properly balanced market, competition would keep profits down to the point at which it made a business viable, but not much more.

That idea was floated by Adam Smith, the 18th century philosopher who invented modern economics. But even he foresaw the dangers:

“As soon as the land of any country has all become private property,” he wrote in 1776, “the landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and demand a rent even for its natural produce.”

That mendacious campaign against Rudd’s modest reforms to control corporate greed would be unlikely to work a second time, though it’s being threatened. The public has now been bitten too often by declining real wages, wage theft, unfair employment contracts, bad corporate behaviour and a public sector sinking into squalor: overcrowded and unsafe hospitals, crumbling schools, universities that blatantly exploit staff and students, shonky private “colleges” replacing TAFEs. And so on.

The opportunity for reform is here. Governments need more revenue, the people demand a fairer society, and the big companies have run out of friends.

Attempts by big business lobby groups – the Business Council, the Minerals Council – to create public panic about Tony Burke’s industrial relations reforms have flopped. The latest, the Closing Loopholes bill, will rightly be scrutinised in the Senate. But early next year, and probably with a few amendments, it will pass into law.

Jim Chalmers’ new White Paper on Employment, which contains the seeds of a quite radical rejection of conventional neoliberal economics, barely raised any opposition at all.

|

| Garnaut ... cursed are the rent-seekers |

But at least it’s on the agenda.

“So while the problem of increasing rents is growing, we are starting to focus on it,” said the economist Ross Garnaut in a recent speech.

“Now is the time to be focused on the rise of rents, policy to slow or reverse the increase, and taxation reform to secure for the public revenue part of the rents that cannot be removed by sound policy.

“Add up all the opportunities for economic reform to reduce economic rents or to tax them efficiently and equitably and you have a transformational economic reform program to increase productivity and equity.”

.png)