We’re getting submarines. So what will we lose?

The navy wins. Losers will be the army, the air force, Medicare, hospitals, schools, the unemployed – and the nation’s safety.

|

| Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus |

“At that kabuki show in San Diego,” said Paul Keating, “three leaders there. Only one is paying: our bloke. Albo.”

After going to extraordinary lengths to avoid being wedged by the conservatives, Anthony Albanese has spectacularly wedged himself. The opposition to the AUKUS project is not coming from the conservatives but from his own side, from former Labor minister Peter Garrett, and Left factional powerbroker Doug Cameron to the manufacturing unions, teachers, the residents of Wollongong who don’t want to live next to a submarine base, to aboriginal leaders worried about a nuclear waste dump on their traditional land.

Two former Labor foreign ministers, Bob Carr and Gareth Evans, and Kim Carr, factional powerbroker and former Industry and Defence Materiel minister, have joined in.

“When I hear the refrain that an Australian flag means just that,” wrote Evans in The Guardian, “and that we will retain complete operational independence in the use of these boats, whatever the context, I can’t help but be reminded of then US secretary of state James Baker’s reply to my call to him as foreign minister at the height of the first Gulf war in 1991. When I suggested that, given the sensitivities involved, it would have been helpful for us to have had just a little consultation before some assets of ours were ordered into a particularly vulnerable location, I was left in no doubt, buddy, that it was Washington running this war, not Canberra.”Peter Dutton thinks it’s a great idea, particularly if it leads to cuts to the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

The split within Labor is too deep and bitter to blow over. The government’s honeymoon is now probably over. There are many losers from this decision, but among those who have been most damaged are Labor’s two most saleable politicians, Albanese and Penny Wong, both from the Left. Defence Minister Richard Marles, from the Right, is triumphant.

With the adoption of Scott Morrison’s big mad idea, Wong and her department have been sidelined. The right-wing takeover of ALP defence and foreign policy has now been achieved.

THE SHIFT WITHIN DEFENCE

Media attention has focused almost exclusively on the submarines and their staggering cost but there is another aspect to all this that needs to be understood: the profound shift in priorities and capabilities that it signals within the Australian Defence Force.

Australia’s defence policy has oscillated between two extremes – forward defence and Fortress Australia.

Forward defence was based on close cooperation with bigger allies – first Britain, then the United States – with the idea of keeping any threat well away from the nation’s shoreline. It was the policy that took us to Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Fortress Australia, in contrast – more politely known as the Defence of Australia policy – is about keeping the continent and its approaches safe from hostile incursions. At its core is self-reliance – the realisation that our great and powerful friends may not come to our aid if it’s not in their own interests.

After the ignominy of Vietnam, the Fortress Australia approach became dominant under the Hawke-Keating governments. The 1987 Defence White Paper said Australia should configure its armed forces to “prevent an enemy from attacking us successfully in our sea and air approaches, gaining a foothold on our territory, or extracting political concessions from us through the use of military force.”

The AUKUS decision is inconsistent with the approach taken by all previous Labor governments of the past hundred years. Huge nuclear-powered submarines are unsuited to the shallow waters surrounding Australia. They only make sense as an integrated element of a much larger – that is, American – force operating against China.

The pendulum has now swung. There is now no question of Australia operating as an independent force to pursue our own national security. We are part of the American push against China. Where it leads, we will go.

The shift in policy requires a substantial shift of priorities within the three armed services. There are two factors at play here. The first is that unless the US intends to invade China – which it won’t and can’t – operations will largely be confined to the sea and, to some extent, to the air. The second is that the submarines are costing so much money that other things within the portfolio will have to be scaled back.

The RAAF is now unlikely to get the next tranche of F-35 Lighting fighters that they’ve been hoping for. The program was to cost around $16 billion – a fraction of the submarines’ cost but still an extraordinarily expensive procurement program. We have 59, with another 13 on order.

Maybe that caution is justified. The F-35 program provides yet another object-lesson in the profligate waste of money inherent in defence procurement.

So far, this expensive piece of kit hasn’t been very reliable, able to fly only about a quarter of the time originally planned. War games conducted by the US military in 2021 simulated what would happen in a war with China over Taiwan. Initially, the commander of the red team, representing China, thought the whole notion of an invasion of Taiwan by China was a fantasy.

“The red commander looked at the playing board and said: ‘This is not rational for China to initiate an invasion, given this posture that I’m facing,’” said senior US commander Lieutenant-General Clint Hinote.

The game went ahead anyway, using a set of assumptions that put the American side on a far better footing than it would be at the moment. One of those assumptions was that the next version of the F-35, not the current or older versions such as those Australia has, would be used.

“We wouldn’t even play the current version of the F-35,”. “It wouldn’t be worth it,” Hinote said. “Every fighter that rolls off the line today is a fighter that we wouldn’t even bother putting into these scenarios.”

The new version, known as Block 4, will include a suite of new computing equipment, enhancements to its radar and electronic warfare systems, and new weapons. Australia now seems unlikely to get these.

Even so, the new version didn’t perform as expected in the war games. Among other problems, the F-35 has a short operating radius of around 1,000 kilometres without refuelling and perhaps half that in combat situations. It would not be able to operate in north Asia without constant refuelling from vulnerable airborne tankers.“For years, Air Force officials have portrayed the F-35 as the aircraft that it would use to infiltrate into enemy airspace to knock out surface-to-air missiles and other threats without being seen,” reported the US publication Defense News. “However, in the war game, that role was played by the more survivable NGAD, in part due to the F-35′s inability to traverse the long ranges of the Pacific without a tanker nearby.”

The NGAD is the Next Generation Air Dominance fighter. It doesn’t exist yet.

Will the nuclear submarines be any more useful?

The army’s losses from this shift in priorities will be far greater than those likely for the air force, and will potentially strike at its basic capability to effectively conduct land warfare.

“The big loser will be the army,” said Professor Albert Palazzo, the former long-serving Director of War Studies for the Australian Army and now an adjunct professor at the University of Canberra. “This has always played out in the past when these kinds of distractions have come up. And it will be that way again.

“I say to army people, ‘If you get one infantry fighting vehicle, consider it a win. Because they may get none. The project may be cancelled.”In March 2018, the army announced that the first of 450 infantry fighting vehicles, a hybrid that’s part tank and part armoured personnel carrier, would be German Rheinmetall company’s Boxer. The army’s media release said 211 would be delivered ready for training to begin in 2020.

Last year, the 450 was cut back to 300. So far, just 25 have been delivered.

In its original form, the project was estimated to cost $27 billion, including the first five years of maintenance. The new IFVs would replace the 257 lightly-armoured ASLAV, now 25 years old, and the 431 M113 personnel carriers that were introduced in 1965 and used in Vietnam. “The M113 remains hopelessly obsolete for contemporary combat conditions,” wrote Al Palazzo last year. “Its blast resistance offers far less protection than the Bushmaster [transport vehicle] and can be deployed only into the most benign environments.”

“The IFVs are critically important,” Al Palazzo told me. “I don’t think they should be cut.

“War is about people. People live on land. War is about exerting control over people, and to exert that control you have to get in amongst the people. That means a land force.

“You can have a nuclear submarine positioned off some island and it fires missiles periodically [at targets on land]. We have seen time and time again that this has no effect. It is not able to shift the will of the targeted people. Just like Londoners during the blitz, just like the bombing of Berlin, it didn’t make them crack.

“When you base everything on a maritime approach, you’re saying that you’re not planning to end the war on your terms, because you don’t have any influence on the other side’s people.”

The new armoured vehicles aren’t the only equipment that Al Palazzo sees as both essential and at risk.

“Tactical drones, which we crucially need, we’ll probably now get a handful. Stockpiles [of various equipment] will be restricted.

“The air force continues to hope they’ll get an additional 24 joint strike fighters [the F-35 Lighting] but the submarine project is just going to suck money from everybody.”

OTHER PEOPLE’S WARS

For most of its history, Australia has been at war somewhere. Leaving aside peacekeeping operations, our longest period of peace was the 21 years between the end of the Vietnam war and the beginning of operations in East Timor in 1999.

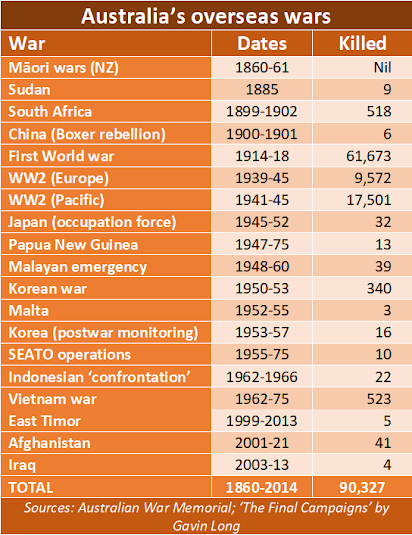

In just one of those wars – against Japan from 1941 to 1945 – was Australia’s own security at stake. The others were other people’s wars in which we joined the fight. The first was the colonial war against the Māori people in New Zealand; the most recent was the war in Iraq.

In the only war in which our own security was at stake, 17,501 Australian troops died. That’s 19% of all Australian war dead since 1860. The other 81% were in wars that did not protect the security of Australia’s territory or the lives and safety of its people.

The toll of service people killed in our overseas wars does not take into account the much larger numbers who were physically wounded and mentally damaged. It does not take into account the veteran suicides, the toll on families, or the massive toll on civilians in the countries in which our forces have operated.

All governments wishing to take their nation to war try to drum up patriotic support, trying to convince the population that their freedom and way of life were at stake, even though they almost never have been. The British have been particularly good at war propaganda, seldom allowing moderation to blur the message.

In 1853 a music hall song helped urge Britain into war against Russia in the Crimea:

That song gave the language the word for aggressive nationalism: jingoism. Australia learnt the techniques of jingo from the Mother Country and learnt the lesson well.

In the South African and First World Wars, Australia saw itself not as an independent nation but still as a British colony. If the Empire called, Australians would answer. That colonial mentality persists today, with the sole difference that from 1942 we transferred our allegiance from Britain to the United States. But our essential colonial status has never changed.

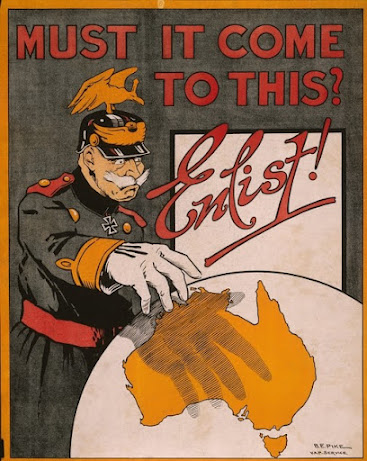

Neither subtlety not truth are ever allowed to get in the way of a war effort. During the First World War it was felt that Australians needed to feel their own country was under threat, even though the war was almost exclusively fought in Europe. Germany’s propaganda at that time was much more measured than ours.

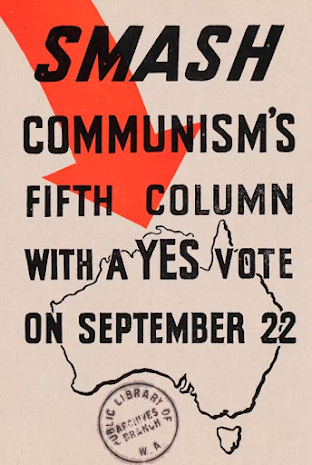

After the Second World War and the defeat of Germany and Japan, a new bogey was needed. Communism was ideal. In the United States, Senator Joe McCarthy led the Red Scare that raged throughout the western world, at its height between 1950 and 1954. That's the period that included the Korean war and the attempt by the Menzies government in Australia to ban communism and ensure ascendancy over the Labor Party, which he accused of being controlled by communists.The government’s propaganda material accused Australian communists (and the ALP) of being controlled by China, where the Communist Party had won the civil war only two years earlier.

Menzies’ referendum in 1951 was a political stunt that failed. But it was a close-run thing, with 50.56% voting against a ban and 49.44% in favour. Majorities in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia were opposed; in Queensland, Western Australia and Tasmania they approved.

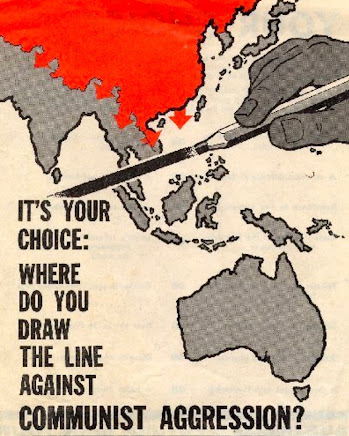

It all re-emerged in the 1960s over the “yellow peril” from red China: the Orange Peril, as some called it. The 1966 federal election was the high-point of jingoistic hysteria, and of support for the Vietnam war and the Liberal government of Harold Holt. The war was strongly and bravely opposed by the Labor Party under Arthur Calwell. The protest movement was led by two prominent left-wing Labor MPs, Jim Cairns in Melbourne and Tom Uren in Sydney.

US President Lyndon Johnson toured Australia five weeks before the election. The visit had the atmospherics of a triumphal progress, embraced by the Liberals and bitterly opposed by the war’s opponents. The tour was responsible for two famous quotations: “Run the bastards over” from the NSW Liberal Premier, Robert Askin, when protesters lay in front of Johnson’s car; and “All the way with LBJ” from Harold Holt, quoting an American election slogan.

Then there was this.

The Sydney Morning Herald and its Melbourne edition, The Age, launched its Red Alert campaign with terms eerily similar to those of the Liberal Party’s pro-war propaganda of the 1950s and 1960s. “Australia faces within three years the real prospect of a war with China that could involve a direct attack on our mainland, but Australia’s defence force is woefully unprepared, the population is complacent and the nation’s political leaders are unprepared to face the dire threats that we face.”It was the latest episode in a long-running story that was

revived by Malcolm

Turnbull in 2017 with his “Australia has stood up” comments made in very bad

Mandarin.

The old China bogey had been woken again. Mike Pezzullo, head of the Defence Department under Peter Dutton, said this on Anzac Day two years ago:

“Today, free nations continue still to face this sorrowful challenge. In a world of perpetual tension and dread, the drums of war beat – sometimes faintly and distantly, and at other times more loudly and ever closer.”

More recently, Dutton said of Australia joining a war with China over Taiwan that it “would be inconceivable that we wouldn’t support the US in an action if the US chose to take that action”.

Pezzullo remains head of Defence under the new Labor minister, Richard Marles.

IN THE NATIONAL INTEREST

It’s usually easier to work out what is actually in a country’s interests than to predict what they will actually do. The two often conflict.

War is not in anyone’s interest. Nobody wins a war. There are only degrees of loss.

War is certainly not in China’s interests. They want to bring Taiwan under control but they’ve been wanting that ever since 1949 and it still hasn’t happened.

There are good reasons for this. Taiwan is separated from the Chinese mainland by 180 kilometres of water. The last time a successful major assault was made across a substantial stretch of sea was on 1 June, 1944. D-Day.Then, the Germans had no effective radar and had been successfully duped into thinking the invasion force would land somewhere other than Normandy. The allied force benefited from cloud cover: for most of the time crossing the English Channel, they were effectively hidden.

China today faces a much more formidable task. Satellites would ensure its preparations for invasion would be visible in real time for the entire world to see. Their journey across the Taiwan Strait would make them extraordinarily vulnerable to attack from missiles, aircraft, submarines and surface ships. Taiwan’s allies would have plenty of time to respond with shattering power.

A blockade of the island would be hardly less problematic. Chinese blockade vessels would also be vulnerable to attack. And history tells us that blockades tend not to work, as the Soviet Union and East Germany found out when they blockaded West Berlin in 1948.

The US and its allies, including Australia, organised the famous Berlin Airlift, supplying the besieged people of West Berlin with supplies from June 1948 to September 1949, when the Russians and East Germans finally gave up. It was a moment of triumph for the West and humiliation for the Soviet bloc.Because they don’t work, blockades have gone out of fashion. The successful ones are in the far past: the French blockade of American ports during the War of Independence, depriving British forces of supplies; the British blockade of France during the Napoleonic Wars; and the Union blockade of the Confederacy during the American Civil War. The attempted U-boat blockade of Britain during World War I was largely unsuccessful; so was its second episode during World War II. The only modern, reasonably successful current blockade is the one conducted by Israel against the Gaza Strip – and that’s a very different situation.

Either an invasion or a blockade would turn the waters off the Chinese coast – and the trade routes on which it relies – into a war zone. Few, if any, cargo vessels would get through – partly because of the risk, and partly because no insurer would cover them.

The Chinese economy, already in serious structural difficulty, would collapse. Imports and exports would stop. Large sections of the population would be returned to poverty and, because China cannot produce enough food to feed its own people, an extended conflict would risk famine.

The Chinese Communist Party would be lucky to survive such a catastrophe. Xi Jinping certainly would not survive.

Not a good idea, then.

But it’s not a good idea for Australia either. This country’s physical security – that is, its assurance that no other country will invade – is not in question. Launching a seaborne invasion of this continent would be suicidal for the invading forces. And no country has the military capacity to do it.

Nor would it make sense for China to disrupt Australia’s sea lanes: they rely on them as much as we do.

Territorial integrity, for any nation, is its bottom line. For us, the question does not arise. So we must move on to the much murkier area of what is in Australia’s broader interests.

Throughout history, most governments have thought this continent and its approaches are too big for us to be able to defend alone. So we have relied on our great and powerful friends – first Britain, then the United States. Participation in the wars of those allies has been regarded as the fee we pay for their protection. Our interests have been synonymous with their interests.

None of this makes sense if we are not under threat now and not likely to be in the future, or if the US alliance makes us less safe rather than safer. There’s a good argument that this is what is happening right now with the Labor government’s uncharacteristic capitulation over AUKUS. For all their blather about sovereignty, has anyone currently in power seriously considered whether we actually had much sovereignty to lose? Or whether, in the rapidly changing dynamics of the Asia-Pacific region, whether we should perhaps be clawing some sovereignty back, rather than giving more of it away?

You don’t need to have a benign view of China to understand that it poses no military threat to us. There is nothing we can do about the disgraceful treatment of the Uighur people, the savage repression of dissent, the subjugation of Hong Kong or the rise of Xi Jinping as dictator-for-life.

In its home waters, China is behaving assertively, rather than aggressively. “As a great state, they want their front doorway clean,” said Paul Keating at the National Press Club. “Just imagine if the Chinese blue-water navy decided to do their sight-seeing six miles off the coast of California. Can you imagine the brouhaha that would go on?”

If Australia became enmeshed in an American war with China, military bases in Australia of relevance to the war would be likely targets for missile attacks. These targets are dotted across the country, many of them close to cities – Brisbane, Perth, Canberra, Darwin and Wollongong.

Our anti-missile defences at all of these potential targets are minimal to non-existent. They are wide open.

“Our current air defence is more than obsolete,” says defence analyst Al Palazzo. “It’s archaic. It’s non-deployable, it’s so old. These submarines, wherever they are based, will be open to the sky. There is no ground-based defence of any of them. There is no planning for how to defend them if we ever meet an adversary launching a surprise attack and dropping a missile on a submarine while it’s tied up against a wharf.”

Dr Palazzo, New York born and raised, looks with alarm and disappointment both at his former country, and his adopted one, edging closer towards war.

“The core problem here is that whenever the United States perceives an adversary, its default stance is to look for a military solution,” he said. “That’s what the US is doing with China right now. They’re trying to understand how they can militarily defeat China.

“We never test any of the other options that are out there, and Australia does the same thing. We’re the junior partner and we pony up some assets to work with the Americans wherever the conflict is.

“And with China there are still other options out there but they’re not being explored. During the Cold War there were all sorts of cultural, sporting and other exchanges designed to defuse the tension. With China there are no such exchanges, and it’s not just the United States. China isn’t setting these things up either.

“It’s not inevitable. But both sides are allowing tensions to escalate, which can only end badly.”

PAYING THE BILL

According to the government, the submarine deal will cost Australian taxpayers from $268 billion to $368 billion between now and 2055. For the first four years – the period of the forward estimates in the forthcoming May budget – it will be $9 billion. Of that, $6 billion of that will be saved from the abandoned French submarine project and $3 billion will come from scrapping other defence purchases.

After that, the real costs begin. Even taking into account savings from the French deal and other military cuts, the second-hand Virginia class submarines to be bought from the US will add between $23 billion and $31 billion to the federal budget over the ten years between now and 2033.

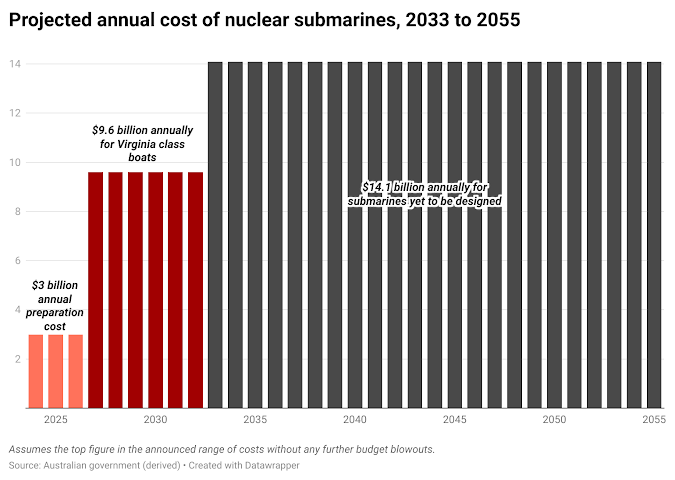

Beyond 2033, the program will cost between $218 billion and $310 billion. On an annual basis, and assuming the higher estimate is the most realistic, the cost will go from an initial $3 billion a year to $14.1 billion when the program is in full swing.

Overall, defence is a middle-order expense to the federal budget. According to the October budget, defence will cost $38.3 billion this financial year. That’s 5.9% of total expenditure.

Clearly, that will not last. Adding $14.1 billion a year to would bring this year’s defence costs to $52.4 billion, an increase of 37% for this single project. Defence would then eclipse education and take up well over 8% of total government expenditure.

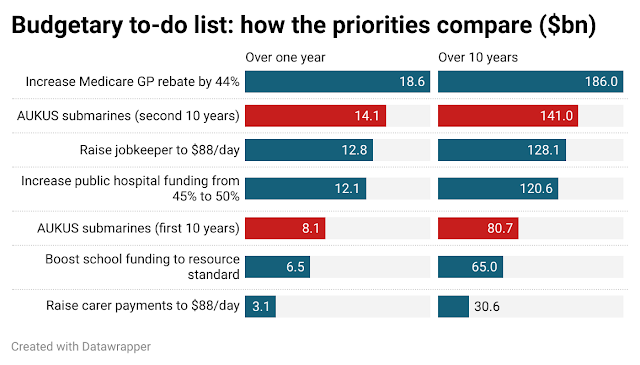

The cost of the submarine project will make it much harder for the government to fund crucial civil projects. The Medicare rebate for GP services needs to go up by 44% to get back to its original level. The current Jobkeeper payment requires unemployed people to live well beneath the poverty line. It has long been Labor policy to increase its share of public hospital funding from 45% to 50% of assessed costs. And disadvantaged government schools are badly in need of a federal funding boost.

All of these measures are vulnerable to cutback or abandonment because of the need to pay for nuclear powered submarines.

The Howard-Costello government gave away the temporary revenue windfall of the last mining boom in the form of permanent tax cuts. As a result, federal governments have spent on average many billions more every year than they have raised in revenue. On top of that was the massive Covid stimulus, blowing out the deficit even further.

Dr Ken Henry, the former Treasury secretary, says the government needs to raise an extra $50 billion in tax every year just to eliminate that structural deficit. That’s without any major new spending initiatives, such as nuclear submarines.

The Prime Minister has also promised to keep the controversial Stage 3 tax cuts initiated by the Morrison government. According to the Parliamentary Budget Office, these will remove another $254 billion in revenue from the budget over ten years.

The submarine deal creates many losers. Winners are harder to find.