Is Labor serious about health? Doesn’t look like it.

Mark Butler’s Medicare “Taskforce” isn’t action on health reform. It’s a substitute for action.

It’s a very old trick indeed, but the electorate still falls for it: when a government doesn’t want to do something, have an inquiry. Then go on doing nothing. In time, the theory goes, media attention will have moved on and everyone will forget about it.

But this is about health. It’s about life and death. It’s not so easily forgotten.

Little in the report of the Strengthening Medicare Taskforce, or in the government’s other plans, seriously or promptly addresses the biggest problems faced by patients needing care: unaffordable copayments at the doctor’s and the pharmacy; hospitals in crisis all around the country; people kept on waiting lists for years; doctors who have closed their books to new patients; delays of weeks to get an appointment; nurses and other staff suffering burnout … and on it goes.

When he released the report of his committee (sorry, Taskforce) Health Minister Mark Butler said this:“Medicare has been the crowning achievement of our health system for 40 years, but it is time for reform. Now is the time to ensure Medicare delivers the kind of primary care Australians expect, both now and into the future.

“Our government has committed $750 million to the Strengthening Medicare Fund, which will be the start of a major revamp of the primary care system.”

That’s $750 million over three years, or $250 million a year.

That’s 0.63% of the total cost of Medicare, 0.23% of what the federal government spends on health and 0.04% of its total budget for this financial year.

To say that more – much more – could not be spent without setting inflation ablaze is pure nonsense. But that’s the government’s line.

WE NEED HEALTH REFORM. THIS ISN’T IT.

The Medicare committee had six meetings and produced a 12-page report (when you discount the blank pages and large pictures of happy patients, it’s actually eight) consisting of old proposals that the participants have been promoting for decades.

Some of these ideas are good ones, though none of them are new. None needed a taskforce to discover them.

The problem with them all is their difficulty in implementation, the savage turf wars surrounding the issue and the cost.

The turf wars have raged for many decades. The Pharmacy Guild wants pharmacists to be able to provide a great many services that doctors now provide, including being able to prescribe medications. The Australian Medical Association and the College of GPs fervently oppose any reduction in the role and power of GPs.

Either of these powerful groups has the power to make life extraordinarily difficult for a government and, particularly, for a health minister. They’ve done so before, many times, and almost always the government caves in.

So the most prominent measure suggested by the committee – super-clinics involving GPs, nurses and allied health professionals under one roof – sounds simple until you look at the complexities.

Will GPs continue to be the gatekeepers for everything? Will a Medicare rebate still be conditional on getting a referral from the clinic’s GP to see the podiatrist or physiotherapist? Who will provide the new, expanded accommodation? Will non-GP practitioners willingly give up their own businesses to become part of someone else’s?

And who will pay?

The committee also talks vaguely about improving digital technology and reforming organisational cultures. Those are very old suggestions indeed, and repeating them yet again reveals the Strengthening Medicare Taskforce as what it is: not action on reform but a substitute for action.

If this report was to be taken seriously as a map for change, it would have to have money attached. Plans and policy strategy documents which don’t contain funding commitments invariably lapse into generalities and platitudes, as this one does.

There is nothing here that addresses the immense and urgent problems facing every practitioner, every nurse, every health administrator and every patient right now. There are many measures that could produce substantial improvements fairly quickly, but the government clearly has no intention of moving on them for the foreseeable future.

THE MEDICARE REBATE

Despite what the government and some committee members have suggested, the Medicare rebate must be increased. When the freeze was initiated in 2013 by the Gillard government (and then extended until 2020 by the Liberals) the rebate for a standard GP consultation was $36.30. It’s now at $39.75, an increase of 9.5%.

But ordinary consumer price inflation has risen in that time by 24.9%. On that basis, the current rebate would be $45.33, or 9% more than it is.

But the under-funding began well before 2013. In 1975, when Medibank – the original Whitlam-era scheme – began, the rebate for a GP consultation was $8.20. If it had risen in line with inflation, it would now be at $65.45, or almost double what it is now.

Doctors have been able to maintain their incomes by increasing the amount they charge patients. Some patients are still bulk-billed, but they tend to be pensioners and others on very low incomes. They are cross-subsidised by other patients who are typically billed for around twice the amount they get back from Medicare.

|

| Shortages .. and not just in the bush |

There’s a legitimate concern about the effects of simply raising the rebate, now that patients have become accustomed to a co-payment. What’s to stop a doctor getting an extra, say, $20 from Medicare, reducing the co-payment by $10 and pocketing the rest?

The government’s answer is not to bother. They have no evident intention of increasing the rebate, using the excuse that doctors will rort the system.

But if the rebate was raised to a reasonable level – and that would mean at least an extra $20 per standard consultation and maybe more – it could be made conditional on bulk-billing that patient. That would at once prevent rorting and massively boost the bulk-billing rate.

THE PBS

Then there’s the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

The PBS copayment is now $30 per script for patients without a concession card. That’s pretty much anyone with a job. Labor cut the copayment to $30 per script, but only because the Coalition promised to do so during the election campaign.

Concessional patients (mainly people on pensions and other government benefits) pay $7.30.

The ABS figures show around 6% of people who’ve gone to a doctor and got a prescription don’t fill it because of that co-payment. That’s about 800,000 people.

As with GP patients, most – 88% – are under 65 and highly likely to have to pay the full amount.

Getting rid of PBS copayments altogether would cost $1.6 billion a year. But all of that could be raised by a fairly simple change to the way the PBS buys drugs.

|

| Generics should save us much more |

That’s the theory.

The problem was that the PBS had no mechanism for taking advantage of this competition and the new low prices. It kept on paying the same amount.

Successive governments have chosen a cumbersome system that reduces the prices of generic medicines, but to nowhere near to the level they could be. The manufacturers like the government scheme – but, over time, it’s costing the taxpayer many billions.

A simple fix would be for the PBS to put the supply of those generics out to tender. That would bring the full benefits of competition in the public’s interest. The PBS pays over three times more for these drugs than New Zealand’s Pharmac, which uses a tendering system.

MORE GPs

There’s a shortage of GPs in most of the country, which is why it can take you two or three weeks to get an appointment – if you can get one at all. The main reason is that too few medical graduates are choosing to go into general practice, preferring instead the high-paid and higher-status world of the specialist.

So why doesn’t the government offer to pay part or all of a student’s tuition costs on the condition that they go into general practice?

The government has announced a pilot scheme in Tasmania for GP registrars (medical graduates who have completed university and hospital-based training and who are now training as specialist GPs) to be employed by the state rather than by individual practices. But because so few medical students choose general practice at all, changing the paymaster during their final training period is unlikely to produce the surge in numbers that the country urgently needs.

ONLY THE FEDS HAVE THE MONEY

In its indifference to the catastrophe in our public hospitals, the Albanese government is unique among all Labor governments of the past hundred years. They have no policy at all on hospitals other than to let them sink further into crisis and chaos.

A federal government that ignores the predicament of public hospitals, as the last one did and the new one still does, is committing an act of gross dereliction. Shuffling off all responsibility to the states is not an answer.

The states and territories do not have the money to run public hospitals as well as to build new ones. The Commonwealth has most of the money-raising powers: income and corporate taxes, mining royalties, the fuel excise, customs duties, tobacco tax, bank levies, alcohol taxes, the fringe benefits tax … and so on.

The states have the GST, various Commonwealth payments and the money they can raise themselves. The most recent Victorian budget shows the state government will rely on Commonwealth funding (which includes the GST) for 49% of its total revenue this financial year. In Tasmania, which has less capacity to raise its own money, the figure is 65%.

There’s little capacity for the states to increase their own taxes and charges. They just don’t have the options they have in Canberra.

But building and equipping hospitals is massively expensive. State governments have only two options – not to build and avoid debt, or build and borrow.

The Victorian government has chosen the second option as the least damaging of two evils. As a result, it has a current hospital infrastructure program amounting to $12.9 billion.

|

| Victoria's immense building program |

Tasmania is the polar opposite. In the last financial year the state government spent just $850 million on its entire infrastructure program, of which $101 million went to health and hospitals. You don’t get much for that these days.

Tasmania’s total infrastructure spend is 11% of revenue. Victoria’s is 26%. That’s the biggest single reason for Tasmania having by far the worst public hospitals in Australia and Victoria having the best.

State governments should not be faced with this appalling choice – to treat patients decently or to rack up huge debt. There’s no need for it – but only the federal government can fix it. And they won’t.

The Albanese government has flatly rejected suggestions that perhaps it ought to deliver the promise made by Julia Gillard in 2011 for the Commonwealth to raise its contribution for each patient’s care from 45% to 50%. Even worse, the higher contribution was actually in place during the pandemic, only to be discontinued by the incoming Labor government.

This won’t be cheap: it will cost around $2.9 billion a year; but neither this, nor the other measures needed to improve hospitals and primary care in the short-to-medium term, would involve a major hit to the federal budget within the next 12 to 18 months. The measure on GP training would take time to ramp up even if it began now. The other measures would need to be negotiated with the states and new agreements signed.

THE CRUEL ALTAR OF ‘BUDGET REPAIR’

The government’s single-minded focus on fiscal restraint ignores the serious possibility that the economy could lurch into a recession. This refusal to spend, combined with the Reserve Bank’s continuing hikes to interest rates, carries dangers that worry an increasing number of senior economists. The ANZ’s former chief economist, Warren Hogan, tweeted this:

“Expect the technical versus actual recession debate to be had in a number of countries. In Australia there is a good chance we will also register a technical recession early 2023.”

And Steven Anthony, a former senior Treasury economist, has put the chances of recession at between 50% and 70%.

If the double-whammy of a gung-ho Reserve Bank and over-tight fiscal policy succeeds in producing a recession – or even a near-recession – the government will face the need to inject more money into the economy to get it going again.

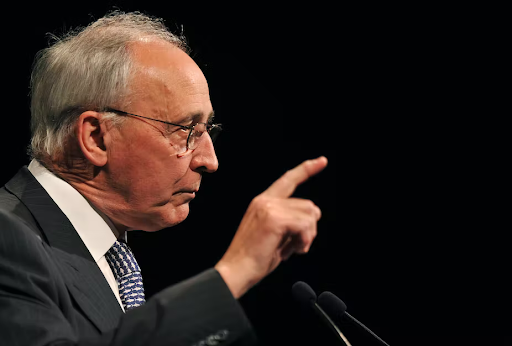

The government will need to raise more revenue, as almost every economist in the land realises. And as Paul Keating has pointed out repeatedly, the government (through its Reserve Bank) could finance spending by creating money. As he said, the bank could buy government bonds and keep the technical debt on its balance sheet – forever if it wanted. There is no need to borrow vast amounts in the commercial financial markets and pay large interest bills.The Commonwealth can do this because they control the currency. The states can’t because they don’t. And higher tax take is essential if this country is to provide its people with the services we can well afford to give them. Measured by GDP per capita, Australia is the tenth richest of all the world’s 190 nations.

But too many of our people are sick, too many are in pain and discomfort, too many staff are burning out and too many people are dying avoidably. That was the predictable result of the previous government’s neglect and uncaring meanness.

We didn’t expect a Labor government to do the same.