In denial: Defence’s giant carbon footprint.

In almost every country, armed forces are responsible for massive greenhouse gas pollution. But governments – including Australia’s – do not disclose that, and do not accurately include defence emissions in their carbon-reduction targets.

Scientists for Global Responsibility, based in Britain, estimates that armed forces are responsible for around 6% of all global greenhouse gas emissions. But following lobbying from the US government, a loophole clause was inserted into the Kyoto and Paris agreements that exempts governments from providing full data on military emissions.

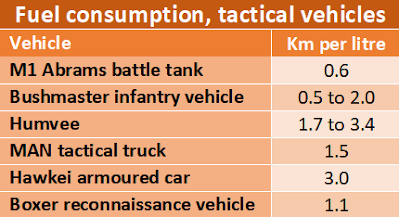

It is certainly true that army vehicles are gas-guzzlers and that they seem to be designed with little attention to fuel efficiency. This has tactical as well as financial and environmental implications: fuel supplies on the battlefield are a major logistical nightmare for commanders.

Fuel consumption figures are not available for some vehicles but this table shows the data for several of those which are published. Generally, these figures are likely to be for road use and as such are optimistic. Off-road use can at least quadruple consumption, as we see for the Bushmaster troop mover.

According to the Australian National Audit Office, the ADF in 2016-17 accounted for 423 million litres of fuel, or 0.9% of the nation’s total fuel consumption. Army is not the dominant user: about 70% was used by the Air Force.

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (pictured) is reported to consume 83 litres of jet fuel per minute, or 5,072 an hour, in normal flight, producing 2.2 tonnes of CO2 per hour. The F-16 fighter burns 1,200 litres an hour in normal flight but 36,430 in full afterburner mode. In that mode, fuel lasts for just 12 minutes.In contrast, a Boeing 737 burns about 2,800 litres an hour in normal flight. But the 737 is a much heavier aircraft – 68,000 kg fully laden, compared with 29,000 kg for the F-35 and 16,875 kg for the F-16.

As this table shows, for every hour an F-35 is in the air, it burns 17.49 per 100 kilograms of aircraft weight. For the F-16, the comparable figure is 7.11 litres and for the Boeing 737, it is 4.12 litres.

Over the five years from 2016 to 2021, Defence spent over $1.8 billion on fuel from seven wholesale suppliers.

The federal government’s Australian National Greenhouse Accounts list only “military transport” (defined as vehicles). For 2020, the figure was 828,000 tonnes (or 0.83 million tonnes). It’s highly misleading.

The most authoritative independent calculations came from a study by Professor Neta Crawford of the Brown and Boston Universities in the United States. The US Defence Department does not report on its greenhouse emissions but according to Professor Crawford’s findings, the Pentagon produced an annual average of 66 million tonnes of CO2 emissions over the ten years to 2018.

The United Kingdom’s Department of Defence does issue some figures but, like Australia’s, they are massive under-estimates. A 2020 report by Scientists for Global Responsibility calculated that carbon dioxide emissions by Britain’s armed services were more than three times the amount claimed by the UK government, and were roughly equal to the total CO2 emissions from the vehicle building industry.

To find a more realistic estimate of Australian defence carbon emissions – and in the absence of any independent studies – the best option is to draw on the Crawford findings of the US situation. Comparing the armed forces of the two nations is not a precise matter, but, with caveats, far from impossible.

The two systems both rely more heavily on technology and equipment than the forces of many other countries (like China, India and Russia, which have large numbers of conscripts and other troops). The equipment is similar and in many cases identical.

So there are three main points of comparison – the overall capability of the two nations’ armed forces, which is calculated by the Lowy Institute; the amount being spent on defence; and the numbers of permanent forces personnel.

Extrapolating from the Crawford estimates of annual US defence emissions (66 mt CO2), looking at relative capability gives us an estimate of 11.1 mt for Australia; comparing expenditure gives 2.85 mt; and comparing personnel numbers gives 2.79 mt.

Each of these methods has its weaknesses. It’s possible that the Australian Defence Force is much more capable, for its size, than America’s. Or it may be that the US uses its people and budget more effectively than Australia. If we assume that the true answer lies somewhere between the extremes, the mid-point is 6.94 mt.

The ADF does not have to report to the Clean Energy Regulator but major companies do. This table shows the top 50 greenhouse polluting companies:

From this, we can see that our mid-point figure of 6.94 mt

would put the ADF at number 16 on the list, with smaller emissions than the

largest coal-fired electricity generators but with more than South 32, Alcoa,

BHP, Fortescue, Shell, ExxonMobil and the major coal miners. As the power companies switch from coal to renewables, the ADF will move further and further up the list of the nation's top polluters.

THE ELECTRIC BATTLEFIELD

Extensive fuel and emissions savings are difficult with present fossil-fuel technology. In land transport, the most probable switch will be to electric vehicles, which offer advantages in pollution reduction and in combat logistics.

The move to electric power need not be restricted to road vehicles. An armoured division of the US Army can consume up to 500,000 gallons (1.9 million litres) of fuel in a single day’s operations.

Matthew Wood, a major in the Australian Army, wrote in an army journal that the ADF would have little choice but to embrace electric power, partly because internal combustion engines will become obsolete and no longer manufactured.

“Australia’s automotive technology and products are predominantly imported from Europe and Asia, countries with a firm vision of a future free of the internal combustion engine,” he wrote.

“So despite Australia’s position on the matter, its consumer market – including Defence – can only consume what is made available by the automotive industry. However, this period of change should not be viewed negatively as the end of a golden era, but rather the beginning of a better one, with better capabilities for both the general consumer and the ADF.”

|

| Abrams battle tank |

The assistant defence minister, Matt Thistlethwaite, was enthusiastic. “The move to acquire hybrid electric vehicles is a major goal for the Australian Defence Force and the government,” he said. But there was no announcement about whether the Australian Army would buy any, or whether current vehicles could be converted.

BREAKING THE TETHER OF FUEL

An important reason why Russian forces were unable to take Kyiv and conquer Ukraine was that their tanks and trucks ran out of fuel. A 65-kilometre armoured convoy stalled in the early period of the war not because of Ukrainian military action but because its fuel supply chains failed.

In March 2003, the main thrust of US forces in Iraq was “operationally paused” because thinly-stretched fuel supply chains were being targeted by Saddam Hussein’s fighters. General James Mattis, later to be Trump’s Secretary of Defense, was in charge of the First Marine Division.

“The military must be unleashed from the tether of fuel,” he said later.

It’s easy to say, harder to do.

.jpg) |

| Palazzo ... fuel is vulnerable |

“Not only do vehicles run on liquid fuel, but all the electronic systems they use – radar, communications systems, the command control devices – run on electricity which comes from diesel generators. So liquid fuel underpins the modern way of war.

“In Afghanistan, which didn’t have any local sources of fuel, everything had to come in across Pakistan and then driven across Afghanistan. That became a problem because it required endless supplies of tanker trucks and distributed into military establishments scattered all over the country,” Dr Palazzo recalled.

“A tanker is very vulnerable. Logistics is the weak point in contemporary military operations. In the past, logistics were behind the line. In Afghanistan, there were no battle lines, so no area was ever really safe. Resources had to be used to protect that supply line.

“In Ukraine it’s not an insurgency, not a guerrilla type war, but the range and accuracy of the various strike systems means that [although] the front line exists, the area behind the front line is also very vulnerable.

“Fuel distribution points are hard to hide, so the rear area is in play to a much greater extent than it was in previous wars.”

Experts have listed key reasons why electrical power can improve combat capability and the survivability of troops:

- On the spot: “You can’t make fuel in military camps but you can make (at least some) electricity.”

- Supply chains carrying volatile, explosive fuel can be highly vulnerable.

- Maintenance is much simpler, quicker and cheaper because electric vehicles have fewer moving parts. They wear out less quickly.

- Survivability: electric power systems can be modular, so elements can be easily replaced. You can have more than one battery or motor, so if one fails you have back-up.

- Modernisation: modular design allows easier, simpler updating. It’s much cheaper and quicker to replace modular elements without having to redesign the whole thing – and without having to discard the entire platform.

- Acceleration: electric motors are much nimbler than petrol or diesel ones.

- Batteries can be used for other things: you can plug power tools and even weapons into the vehicle’s battery.

- Adaptability: electric tanks would be computer controlled, giving different performance modes for various situations – road, energy-saving, off-road and so on.

- Under water: electric motors don’t breathe air, so vehicles can be completely submerged.

- Harder to detect: electric vehicles produce less heat, have no exhaust systems and are quieter. Thermal cameras would find them hard or impossible to detect.

“The military are caught at a turning point,” Albert Palazzo told me. “They have an existing fleet, and they’re buying replacement vehicles that fit a particular paradigm.

“In Australia and in the US, it hasn’t attracted a lot of attention because they’re focusing on achieving the combat outcomes they want. To risk that by going in a whole different direction hasn’t been judged as a worthwhile effort.”

CLIMATE-WRECKING AIR FORCES

But the really big potential savings in armed forces’ fuel consumption are in the air. In Australia’s case, the RAAF is responsible for around 70% of military fuel consumption.

Electric aircraft will not be possible without many technological breakthroughs. But technology already exists to do better in the military sector.

Military aircraft have been developed solely with combat performance in mind, no matter what the cost in fuel and emissions. Climate, certainly, has never been a goal. Contrast that with the commercial imperatives of commercial airlines – and therefore of passenger aircraft manufacturers – to improve fuel efficiency. They are also under immense pressure to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

The average fuel burn of new commercial aircraft fell by 45% between 1968 and 2014, an average improvement of 1.3% a year. But with military aircraft, it has gone the other way.

This has resulted in serious operation limitations for high-performance aircraft. An article in the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s magazine put it this way:

|

| F-35 refuelling .. high performance, short range |

Reduced range increases the need for mid-air refuelling from large, vulnerable airborne tankers.

Albert Palazzo summarises the problem: “Getting a slight performance edge may mean the difference between success and death. So performance is where the emphasis has been.

“Now, going forward, perhaps that will change.”