Rednecks on the run: how Australia transformed itself.

The bookies don’t think much of Peter Dutton’s chances of becoming Prime Minister. Shortly after the last election, Sportsbet put the chances of a coalition victory in 2025 at $3.10. That’s probably generous.

Dutton, and the values he represents, are sinking further into spluttering irrelevance. But not long ago, those conservative values – the doctrines of Howard, Abbott, Hanson and the Christian Right – appeared to capture the nation’s mood. Until they didn’t.

Exploiting fear of a scary “other” has been a powerful tool of opportunist politics through the ages. When the threat is external, it can lead to war; when internal, the “enemy in our midst” mindset leads at best to discrimination. At worst, it can end in murder: examples range from colonial massacres of aborigines and Chinese, to gay-bashing murders in Sydney in the 1990s, and to the demonisation of asylum seekers in the past twenty years.

The antidote is visibility. When the “other” is seen to be an ordinary human, fear dissipates.

In a little over a decade this country has changed strikingly, unmistakably and forever. Old fears, once-visceral hatreds, have suddenly lost their power. Where now is the panic about terrorists? Boat people? Asian immigration? Muslims? African gangs?

Climate change is, at last, taken seriously. People of the same sex can marry, have children, adopt. Half the population no longer believes in God. We want drug users to get treatment, not prison sentences. It’s as if the new century has finally arrived.

Change the government, said Paul Keating, and you change the country. But it’s the other way round. The great, underlying shifts of society can only be created by the mass of the people. The politicians of the day can manipulate those fundamental trends but can do little to create or control them. The election of a progressive federal government is the culmination of all this, not the cause.

Imagine a clock, ticking away, the pendulum swinging back and forth within an apparently unchangeable range. Now step back. From a distance, you can see the whole clock is moving, bodily and inexorably, towards the left.

Just like the apparently unchanging pendulum – tick-tock, right-left – the political swings between the left and right, Labor and Liberal, have the ground moving beneath them.

History takes all of us with it, conservatives and progressives alike. And history, like my imaginary clock, moves to the left.

We can trace the pathway of change by looking at its two main markers: race and religion.

RACISM’S DECLINE

“I believe we are in danger of being swamped by Asians,” said Pauline Hanson in her notorious first speech to parliament in 1996. “They have their own culture and religion, form ghettos and do not assimilate … A truly multicultural country can never be strong or united.”

Those thoughts were not new. The White Australia Policy may have been officially dead by then, but non-white migrants still suffered massive discrimination. The official policy of multiculturalism, embraced by the Hawke and Keating governments, was passionately opposed by conservatives.

|

| Blainey ... 'too many Asians' |

“We are surrendering much of our own independence to a phantom opinion that floats vaguely in the air and rarely exists on this earth,” he wrote later. “We should think very carefully about the perils of converting Australia into a giant multicultural laboratory for the assumed benefit of the peoples of the world.”

Opposition to Asian immigration and multiculturalism was based on two claims: that it eroded Australia’s cultural and political independence; and that it would change the nature of Australian society for the worse.

John Howard bought in. In 1988, as leader of the Liberal opposition, he introduced a One Australia Policy, calling for an end to multiculturalism; and on ABC Radio, he called for Asian immigration specifically to be reduced.

The National Party leader, Ian Sinclair, agreed. “I certainly believe that at the moment we need ... to reduce the number of Asians.”

The 9/11 attack in New York supercharged the fears and hatreds, but this time it had shifted to Muslims and refugees. Howard was quick to take political advantage.

|

| Refugees lined up on deck by Australia's SAS |

“They sent a plane to direct us to the sinking boat,” the

Tampa’s captain, Arne Rinnan, recalled later.

“When we arrived it was obvious

to us that it was coming apart. Several of the refugees were obviously in a bad

state and collapsed when they came on deck to us. Ten to twelve of them were

unconscious, several had dysentery and a pregnant woman suffered abdominal

pains.”

But there had been an increasing number of refugees arriving in Australia by boat; radio shock-jocks and conservative politicians eagerly exploited the public’s concern. Howard, struggling in the polls and with an election looming, seized the issue. The Tampa was refused permission to dock, and the refugees were sent to Nauru.

The Labor opposition leader, Kim Beazley, caved in at once, handing Howard the election.

|

| Jones ... 'come to Cronulla' |

On Sunday 11 December, some 5,000 people gathered at North Cronulla beach for Australia’s first major race riot since the 1930s. By the end of the day, 26 people had been treated for injuries and 16 people were charged with a total of 42 offences. A police officer and a man of “middle-eastern appearance”, who had been seriously assaulted, were taken to hospital. Two paramedics were injured when their ambulance came under attack.

There was a payback attack by young men from south-western Sydney. Over the next few days there were further assaults and arrests.

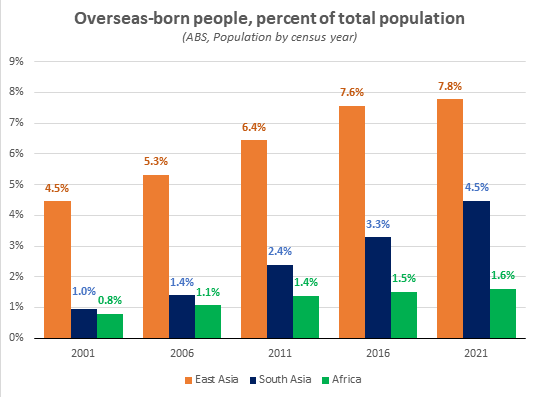

As it happened, though, Asian and middle-eastern immigration continued. By 2021, 12.3% of the resident population were born in east or south Asia. Despite this, and despite our massive economic involvement with Asia, Australia has demonstrably retained its independence. The culture, though enriched, endures; and our sense of national identity lives on.

In the two decades following the Tampa, many of the fears and hatreds subsided. Asylum seekers are increasingly no longer seen as a threat but rather as people in urgent need of humanitarian assistance.

A study commissioned in 2015 by SBS found a large majority thought Australia should help refugees fleeing persecution in their homelands, though a smaller majority also supported the bipartisan policy of boat turnbacks.

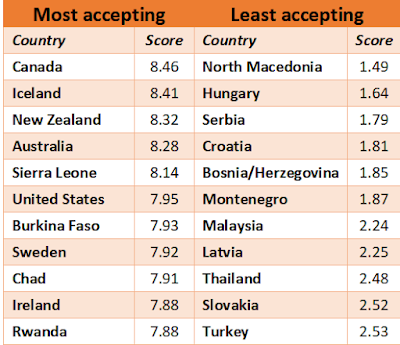

In 2019 the Gallup World Survey found that of the 145 countries polled, Australia was the fourth most-accepting of migrants, with a score of 8.28 out of a possible 9. This is a significant increase from the previous survey in 2016, when we were in seventh place with a score of 7.98

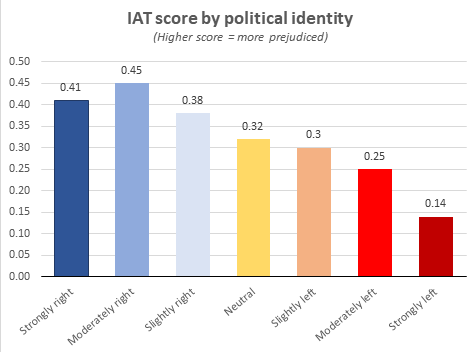

The least-accepting nations were mostly those in central Europe which were most directly impacted by the refugee crisis of 2015. Australia, with no land borders, is unlikely to ever be confronted with such a flood of desperate humans, whether or not they arrive in boats.An interesting study by researchers at the Australian National University has attempted to quantify underlying, unconscious bias rather than the overt attitudes covered by most surveys. They used the Implicit Association Test (IAT), a tool to compare reactions to an in-group (in this case, Caucasians) versus an out-group (indigenous Australians). The study showed high correlations between underlying bias and both political leanings and religion.

We need to be careful in drawing too many conclusions from these findings. Unconscious bias does not necessarily imply conscious belief or overt behaviour

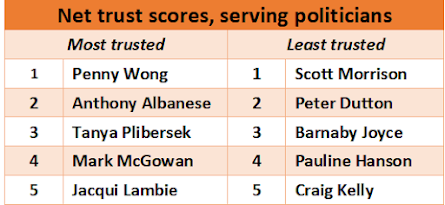

Shortly before this year’s federal election, the Roy Morgan polling company released findings on the most- and least-trusted Australian politicians. The most trusted was Penny Wong, a lesbian woman of Chinese descent. The least trusted was Scott Morrison, followed by Peter Dutton.

RELIGION IN DECLINE

Throughout human history, religious differences have formed the basis of almost continual wars, persecution and discrimination. Freedom of religious belief has long been a pre-requisite of any liberal democratic society, but those benefiting from that freedom do not always extend it to other social groups. Therefore, it is plausible that the decline in religious affiliation is causally related to the decline in the demonisation of fringe groups, including refugees and minority ethnicities.

Christianity has been in decline for several decades but the fall has gathered pace in the past ten years. At the same time, the proportion of people with no religious belief rose. When the next census is taken in 2026, we can expect non-believers to outnumber Christians.

Other religions are not filling the gap. They have increased, but from such a small base as to have little overall impact.

The national figures are distorted somewhat by the relatively high levels of religious belief in NSW, which is most probably a reflection of migrant communities. In Tasmania, which has a lower proportion of overseas-born migrants, half the population has no religious belief. Despite a high profile, Pentecostalism is not making ground, flatlining at around 1% of the population.

Despite widespread improvement, bias remains. The hangover from the panics over terrorism has led many Australians to see Islam – and Muslims in general – as a threat. A survey by the commercial research company Statista showed 40% held negative attitudes to Islam. Interestingly for a nominally Christian country, Christians were the second most-disliked group.

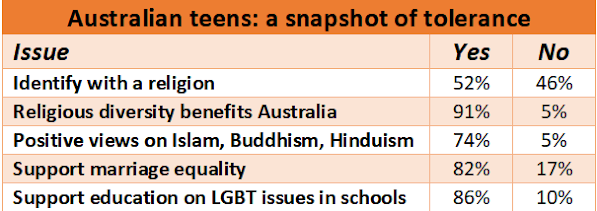

There are some signs that this is abating. The Generation Z Study of Australian teenagers, commissioned by the ANU, Monash and Deakin Universities, revealed young people hold overwhelmingly positive views on Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism. According to the study, it was 74% in favour, 5% against. They can be expected to carry their more tolerant attitudes through life,Teens are also somewhat less likely than the whole population to follow established religion, though many are experimenting with alternative spiritual beliefs.

In the “plebiscite” on same-sex marriage in 2017, 62% of the 18+ population voted in favour and 38% against. That was regarded as a triumph, but young people are much more progressive. According to the study, 82% support marriage equality and only 17% oppose it. And they reject the conservative panic about teaching about LGBT people and issues in secondary schools by 86% to 10%.

IS AUSTRALIA STILL A RACIST COUNTRY?

There are two sides to this question. On one side are the Tampa affair, the Cronulla riots of 2005, the “intervention” into aboriginal communities, the cruelty to refugees and the successful political exploitation of race-based fear-mongering.

On the other side are tough and universal anti-discrimination laws, a belated but evident improvement in the diversity of parliamentary representation and workplace composition, and a profound shift – revealed by a large body of research – in the way Australians treat each other.

Race-baiting is no longer a viable political tactic. Racist shock-jockery is out of fashion; tabloid nastiness has to find other targets. It is almost inconceivable that the Cronulla riots could occur today. As this story has attempted to show, the nation has changed.

Tolerance and its opposite are states of mind that tend to apply generally. If someone dislikes one outsider group, there’s a fair chance they’ll dislike others too. As fear of one group dissipates, so too does antipathy to others. The overwhelming support for marriage equality, and Australia’s high and improving ranking on welcoming migrants, can be seen as aspects of the same outlook.

There is racism in every country. But a whole nation cannot realistically be called racist unless it is a defining characteristic. If Australia is a racist country, then which country isn’t?