The loneliness of the long-distance health reformer: Stephen Duckett on politics, bureaucracies and the pandemic.

Anyone who still thinks Australia’s health system is fit for purpose really hasn’t been paying attention.

Despite all the blather, Covid isn’t the main problem. It’s a symptom of the malaise more than the cause. Stephen Duckett – health economist, academic, top-level health bureaucrat and policy wonk – put it this way:

“A decade ago, you might say one or two states’ [hospital systems] were in a parlous state. But what we’re seeing now is that every state’s hospitals are overwhelmed. It’s not an issue of some states good, some states bad; but rather that the system is not coping well with the pandemic. So we’ve got to say why is this, what do we need to do about it.”

Unfortunately, getting reform actually done is desperately difficult. For a decade until April this year, Stephen led the health program at the Grattan Institute, the university-oriented national think tank. In report after report, he and his colleagues presented well-documented analyses of the problems facing the health system, and suggested ways they could be overcome.

The crisis in private health. Addressing GP shortages. Palliative care. A proposal for a comprehensive public dental scheme. How to save billions on the PBS. Improvements to hospital funding that would achieve more with the available cash. Making hospitals safer. Using pharmacies better. And so on.

Most of these reports got widespread media attention but they had little effect on government policy. The inequities, inefficiencies, waste and stupidity that bedevil the system continued. Turning around a supertanker is dead easy, compared with this.

Partly, that can be put down to a succession of governments that were not conducive to serious and positive reform – the coalition governments preferring to subsidise the private insurers while allowing Medicare and public hospitals to wither, and the Rudd-Gillard government too chaotic to achieve much of substance.

ADVENTURES IN BUREAUCRACY

It’s easier when you’re on the inside of a more orderly outfit that is open to reform, as Stephen was as head of the Commonwealth Department of Health during the Keating government. A quirk accompanying his appointment showed how insular and out-of-touch the public service had become.

He was told verbally by the secretary of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet – the official head of the public service – that he’d got the job. Then silence.

“A week later I spoke to him again and said: ‘Am I going to get a letter of appointment?’

“And they had not appointed a secretary from outside the public service for more than a decade, so they had no process for making external appointments. What this tells you is that there was an insularity in the Commonwealth Public Service that led to a remoteness from reality.”

“What was interesting is that I’d come from the state bureaucracy [as head of the Victorian public hospital system] and I had different ways of working and different insights.”

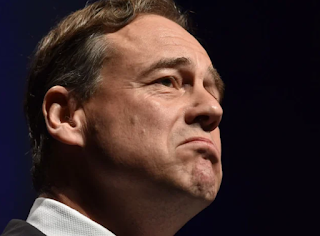

|

| Lawrence ... 'easy to work with' |

“I remember talking to one of my senior staff and I said: ‘We should just do x. I know how the states are going to respond.’ And they said: ‘That can’t be: they’re not going to do that’.

“And I said: ‘Trust me. I know how they think. I know how they will respond.’

“The fact that there were fewer people from outside joining the Health Department inhibited the way it worked, and inhibited the choices that ministers could think about.

“The department had a reputation of fighting on the wrong sort of issues, not fighting on policy issues. So part of my job was to improve the credibility of the department.”

In the previous decade Paul Keating – then Treasurer, now Prime Minister – had overseen massive cuts to the federal budget. By 1993 that phase was over, and the time to rebuild had arrived.

“He didn’t place a great priority on health. He was more interested in industry reform; health was seen as a sideshow. So Carmen Lawrence had a lot of autonomy in what she could do.

“She was a very easy minister to work with. She encouraged me that if I thought her advisers were going in the wrong direction to be open and active about it, and to raise it with her directly. I had a very good relationship with her, so if the senior staff [in the Health Department] were uncomfortable about something, I could go to the minister and ask: ‘Is this what you really want?’”

It didn’t last. Three years later, the Keating government was out of office and Stephen had a new minister, Michael Wooldridge and a new Prime Minister, John Howard.

Wooldridge told me at the time that although he disagreed with Stephen’s personal political views – which were seen as somewhat left-wing – he was an effective and highly professional secretary who would implement the new government’s policies. The decision to sack Stephen – one of five secretaries swept from office – was made by Howard, not Wooldridge.

A REFORM SAGA

It would take more than a decade, and the election of another Labor government, for Stephen’s most significant reform initiative – a revolutionary method of hospital funding – to be enacted. We know it as activity-based funding. It was the only major element of Kevin Rudd’s grand health reform plans to survive into reality. But it’s the way almost all public hospitals are now funded.

The Commonwealth now pays 45% of the theoretical cost of treating each patient. It hasn’t been without its problems and its critics, but it at least brought a new level of transparency, accountability and efficiency to an area that costs state and federal governments well over $60 billion a year.

When he was in government, Stephen spent a good deal of his time refining this scheme, setting up a whole branch within the Department of Health to do so. But the saga underlines how difficult it is to reform a system with too many moving parts and too many vested interests.

|

| Hunt ... don't think, obey |

Martin Bowles, one of Stephen’s successors as secretary, failed to follow those orders to Mr Hunt’s satisfaction, and retained a small policy unit within the Health Department. The one-sided shouting match that ensued between Hunt and Bowles led to the departure of yet another secretary of health.

As the need for health reform has intensified, the political will to do anything has fallen further and further behind. There is now a unnerving backlog of measures that are difficult, expensive and utterly necessary.

FUMBLING THE COVID RESPONSE

The pandemic was always going to be serious, but it should not have had such a devastating impact on healthcare. The capacity to deal with crises had been leached, over decades, from every element of the system from general practice to tertiary teaching hospitals. We are now paying the price of those years of parsimony and wilful neglect.

Stephen believes that ministers who shut their departments out of decision-making set themselves up for failure. An example is the vaccine rollout in 2021, a major scandal that inflicted irreparable damage on the government and undoubtedly cost lives.

At least in part, he blames the former government’s insularity and ineptitude for the current policy paralysis in addressing the re-emergent Covid crisis.

“One of the legacies of the Morrison government was that it undermined the social license to act, and it just made it so much more difficult to do anything. But, having said that, it is now incumbent on the new government to start moving away from that individual responsibility thing.

“We know, for example, that ventilation is really important for reducing the spread of the virus. Now, it’s nonsense to think about ventilation as being a matter for personal responsibility. It’s quintessentially a public health issue.

“On masks, we need to – at least – be talking up mask-wearing more than we have, and at some point decide we have reached a trigger-point and require everybody to wear a mask [in particular settings] because not enough people are.

“You’ve got to be talking up the public good, rather than individual responsibility. After all, that is what public health is all about.”

Anthony Albanese has promised to restore policy capacity across the public service and to bring it back into decision making. So far, though, Labor has been reluctant to take a lead on the pandemic response. It’s not a good omen.

Reform is so difficult, and so expensive, that it takes an extraordinary level of political will to achieve anything substantial. And it usually takes quite a lot of money.

The new Treasurer, Jim Chalmers, is setting the scene for a horror budget. It will, he says, be “confronting”.

If the Albanese government lasts long enough, we may at last get some of the reform we desperately need. Just not yet.