No God, please, we’re Tasmanian.

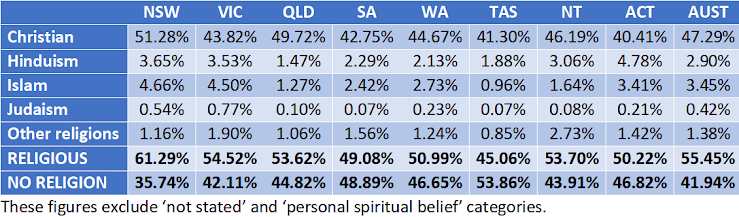

Tasmania has become the first – and only – Australian jurisdiction in which the majority of people no longer believe in God. According to the census, 54% of Tasmanians have no religion. That’s 11% higher than the national average. No other state or territory comes close.

And Tasmanians are dropping religion much more quickly than other Australians. At the beginning of the century, Tasmanian non-believers outnumbered those in the rest of the country by only 1.8%. Twenty years later, that gap has increased to 11.2%.

(In this post, 'not stated' and 'inadequately described' categories are distributed pro-rata.)

The trend is evident across all major religious categories. The Catholic Church lost 11% of its adherents in just five years from 2016 to 2021, but even that was a better performance than the main protestant denominations: Anglicans (down 23%) and the Uniting Church (down 25%).

Expressed as percentages, the two main non-Christian religions – Hinduism and Islam – did spectacularly well, increasing by 281% and 98% respectively over the five years, as Tasmania became more multicultural. But that was from a very low base and made little difference to the overall picture of a general abandonment of religion.

Nationally, the Pentecostal and Mormon churches have fared better than the mainstream Christian denominations – but not in Tasmania. Taken together their numbers have fallen by 14% – less than the Anglicans but more than the Catholics.

Although religious adherence differs somewhat across the state, the trend everywhere is evident and profound. In just five years Braddon, covering the north-west and west, has gone from being one of the most religious of the five Tasmanian electorates to being its least religious. Almost 60% of people in that part of the state no longer describe themselves as having a religious affiliation.

These results indicate not only that a profound and rapid social change is under way, but also that it is more advanced and quicker in Tasmania than anywhere else in the country. The impact of this change on the nation’s smallest state has gone largely unremarked. But its wider implications – for the sort of society we live in, the way we regard ourselves, and the kinds of government we need – require some serious and urgent attention.

The reasons why this change is happening so much faster in Tasmania are not obvious. The state has somewhat different demographics, but it always has. That hasn’t changed enough in five years or even in twenty to explain this shift. In fact, those demographic differences from the rest of Australia should produce the opposite result: Tasmanians are older, less affluent, less educated and whiter than the average. But while this may once have produced a more conservative society, that does not appear to be the case any more.