Russian oligarchs, sanctions, money laundering – and the art market.

If you had a lazy $280 million just lying around, you could buy 199 average-priced houses in Sydney, or 396 in Hobart.

You could pay for 10,700 people to have hip-replacement operations.

You could fund Foodbank to provide 560 million meals for people who can’t afford to eat.

Or you could buy an Andy Warhol screenprint.

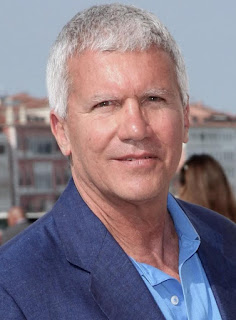

Shot Sage Blue Marilyn was recently sold at Christie’s in New York for $US195 million, or $A280 million, to a prominent art dealer, Larry Gagosian. It was originally sold in 1963, from a gallery Gagosian later owned, for $US1,800. He has been described as one of the most powerful people in the art world and lives in New York State in a mansion called (yes, really) Toad Hall.

|

| Gagosian |

Despite being universally described as the buyer of Shot Sage Blue Marilyn, Gagosian clearly did not buy it for himself or use his own money to do so. The price would have taken a third of his net worth, which is estimated at $US600 million.

And the “shot” tag for the various-coloured Marilyns?

The Los Angeles Times put it this way: “Four of them (all but the turquoise) were stacked in his studio when a friend brought performance artist Dorothy Podber to Warhol’s studio. She asked to shoot the four works, and when Warhol obliged, thinking she was going to take pictures, she pulled out a gun and shot the canvases, piercing holes in several of them. They were subsequently repaired, but the name stuck.”

Maybe she had a point.

|

| Basquiat: off to Russia? |

A year before, another 20th century painting, In This Case by Jean-Michel Basquiat – another Warhol protégé – raised headlines around the world when it sold (again, at Christies in New York) for $US 93.1 million ($A134 million). Personally, I’d pay good money to get rid of the thing, but a “private buyer” obviously thought otherwise.

Then there was the Botticelli. A small portrait – A Young Man Holding a Roundel – was bought at Sotheby’s in New York by a “Russian private collector” for $US92.2 million ($A132.3 million).

The potential for high-stakes chicanery has been worrying authorities internationally, but in the United States – where most of the big sales happen – there’s been little real action.

THE LID LIFTS – A LITTLE

Two years ago, a bipartisan committee of the US Senate reported on how Russian oligarchs used the secrecy of the art market to evade international sanctions and to transfer illegal wealth. The art business, they said, was the largest legal, unregulated financial market in the United States.

“It is shocking that U.S. banking regulations don’t currently apply to multi-million dollar art transactions, and we cannot let that continue,” said the committee’s chair, Senator Rob Portman.

“The art industry currently operates under a veil of secrecy allowing art advisors to represent both sellers and buyers masking the identities of both parties, and as we found, the source of the funds. This creates an environment ripe for laundering money and evading sanctions.”

Although the four big auction houses – Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Phillips and Bonhams – all have anti money laundering controls, these are purely voluntary and largely ineffective. The auction houses treat an art dealer or agent as the principal purchaser, even if there is reason to believe they were working for an undisclosed client. Legislation to tighten regulations is stalled in Congress.

Private art dealers, like Larry Gagosian, are not subject to any anti money laundering controls or code of conduct.

Shady law and accountancy firms in tax-haven countries play a central role. Data made public in the massive Panama Papers leak of 2016 allowed the American senate committee to trace the activities of Arkady and Boris Rotenberg. The Rotenbergs are Putin cronies who were sanctioned by the US, Australia and other countries in 2014.

|

| Baltser ... the Moscow connection |

Within a short time, Baltser had bought over $US18 million ($A26 million) in art with money from Rotenberg-linked shell companies. The paintings included Magritte’s La Poitrine, bought in a private sale, and another swag of pictures bought at a single Sotheby’s auction in New York.

The Rotenbergs continued to move at least $US91 million ($A130 million) through the US financial system following the imposition of sanctions in March 2014.

The further you move up the art market food chain, the more likely you are to be swimming with sharks.

LOTS OF PEOPLE MAKING LOTS OF MONEY

Too many people are making too much money for this to be stopped quickly or easily. Let’s take the auction houses first.

There are two prices for every item that’s sold – the hammer price and the price the buyer pays. The hammer price is the one quoted by the auctioneer when the gavel comes down.

But sellers don’t get the hammer price and buyers don’t pay it. It’s a starting point, nothing more.

Christie’s, for instance, negotiates a percentage fee with the seller. That fee increases if the item sells for more than the estimate. The seller also pays taxes, transport, insurance and so on.

The buyer is hit with even more costs. The “buyer’s premium” is 26% of the hammer price, reducing to 14.5% above $6 million.

So, for handling the Warhol picture, Christie’s would have been paid $US28,305,000 ($A40,232,000) by the buyer and several million more by the seller.

The middleman – in this case, Larry Gagosian – would have also charged a hefty fee. We’ll never know what that was, but it would be unlikely to be less than $US15 million, and probably more.

IS AUSTRALIA NEXT?

The Australian art scene, though vastly smaller, remains vulnerable to money launderers, sanctions busters and financers of terrorism. Australian law has the same weaknesses as America’s: the art market is not covered by anti money laundering requirements.

Paintings have sold at Australian auctions for as much as $6 million (Henri’s Armchair by Brett Whiteley). In all, 33 Whiteley works have sold at auction for over $1 million each; several other artists – Streeton, McCubbin, Brack, Smart – are not far behind, and it’s become common for individual paintings to change hands for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Last year, the art auction market in Australia was worth $121 million, and that’s without private sales and sales through commercial galleries. Art in Australia is a substantial financial market – and it’s wide open for exploitation.

Those most likely to use this pathway are not Russian oligarchs but drug dealers, terrorism financiers and Asian organised crime. Until now, they have favoured the weakly regulated casinos to wash their cash. But the scandals involving Crown and Star are leading to tighter supervision and tougher laws.

Cash transactions over $10,000 must be reported to AUSTRAC. It’s now an offence to split transactions to avoid scrutiny, and banks have systems to detect that.

As criminal groups have more difficulty in converting their money into a usable form, they will inevitably turn to newer methods. The art business is ripe for plucking.